The Diesel Crack Spread: Venezuela's Move, China's Crisis

Venezuela's Merey 16 crude is gone. Shandong's cokers are starving. The diesel crack spread is widening because the molecules are wrong.

The diesel crack spread started widening on January 3rd. Not oil prices. Diesel specifically.

Most traders missed it because they were watching headline Brent, which barely moved. The signal was buried in the derivatives market, flashing a warning that only matters if refineries are configured a certain way.

Chinese refineries in Shandong province are configured exactly that way.

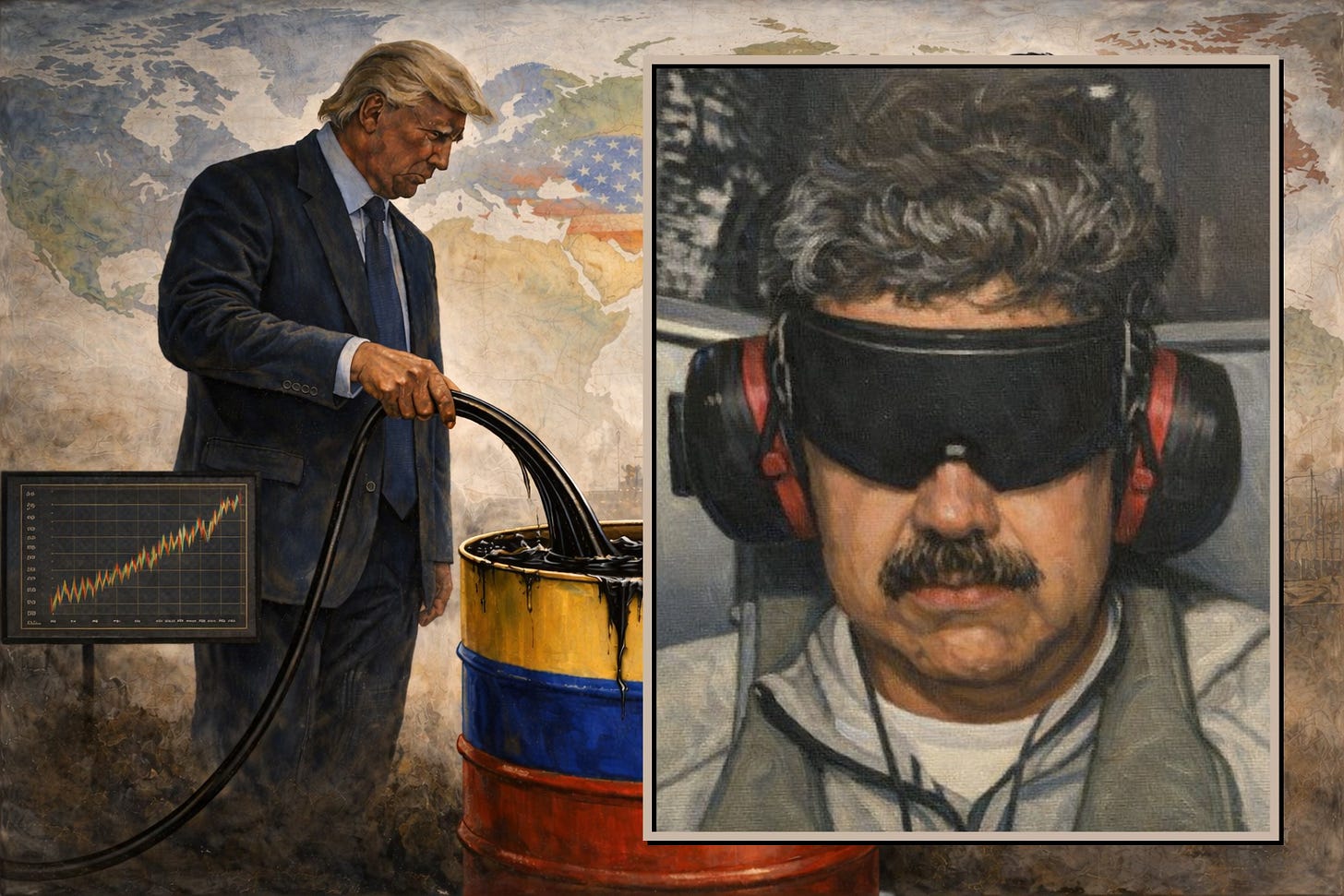

The United States just executed a surgical strike on China’s energy security, and Beijing is realizing it too late.

Operation Absolute Resolve removed Nicolás Maduro from Venezuela in under thirty minutes. Delta Force, Night Stalkers, the full apparatus. The justification was narco-terrorism charges. The real target was the commodity bridge linking Caracas to the industrial coast of East Asia.

Venezuela’s Merey 16 crude isn’t normal oil. It’s extra-heavy, sulfur-laden, and so contaminated with metals that processing it requires specialized refinery equipment costing billions to install. Think industrial-scale chemistry sets built specifically to handle trash.

China’s Shandong refineries were built for exactly this garbage.

They invested in delayed coking units because Merey 16 traded at massive discounts to benchmark crude. The business model was sanctions arbitrage: buy distressed Venezuelan barrels that Western majors wouldn’t touch, process them through cokers, sell diesel into a hungry market. The profit came from the discount. The physics worked because the refineries were designed for heavy, sour, acidic feedstock.

That arbitrage no longer exists.

The China Development Bank extended somewhere between $17 billion and $19 billion to Venezuela under the Chavez and Maduro regimes. The loans were resource-backed, meaning Venezuela didn’t repay in cash. It shipped oil directly to Chinese state firms, and those oil sales serviced the debt.

No cash changed hands. Just molecules flowing east across the Pacific.

With Maduro in U.S. custody and Washington claiming it will run Venezuela temporarily, that closed loop is now a black hole. The person who signed the loan guarantees is facing narco-terrorism charges in New York. A transitional government in Caracas could declare the loans odious debt: borrowed by a criminal regime, used for repression, non-binding on the successor state.

The precedent exists. Washington used the same argument to clear Iraq’s debts after Saddam fell.

China is staring at a potential total write-off. The collateral was Venezuelan crude. The collateral has been kinetically interdicted.

The Shandong refineries cannot simply switch to light sweet crude from Texas or the Middle East. The thermodynamics don’t work. Light crude has very little residual oil. Running it through a coker leaves the most expensive equipment idle. The product slate shifts toward gasoline instead of diesel.

If the market needs diesel, processing light crude makes the shortage worse.

These refineries were built with high-alloy steel to handle the acidity and metal content of trash crudes. Using expensive, low-acid light crude in those systems is like installing titanium exhaust pipes on a diesel truck and then fueling it with premium gasoline.

The obvious substitute is Western Canadian Select. It’s heavy, sour, acidic. Chemically similar to Merey 16. The Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion added export capacity to Canada’s Pacific coast, making it accessible to Asia.

But there’s a problem.

U.S. Gulf Coast refiners also need heavy crude. Marathon, Valero, and the rest of the complex refining sector were counting on Venezuelan barrels. With those barrels removed, they’ll bid aggressively for Canadian supply.

Shandong refineries will find themselves competing with American majors who have better credit, better logistics, and state-level political support.

The discount on Canadian crude will narrow. The margin advantage evaporates. Refineries that survived on cheap sanctioned crude will now pay market rates, erasing the profitability that kept them solvent.

Beijing has been trying to consolidate the independent refining sector for years, shutting down smaller plants and transferring capacity to state-owned enterprises. The collapse of the Venezuelan supply chain accelerates this process involuntarily. Some refineries will go bankrupt. State firms will acquire the assets.

The industrial policy goal is achieved, but through humiliation rather than strategy.

Meanwhile, Chevron operates under a specific U.S. Treasury license, exporting Venezuelan crude directly to the United States. That flow continues uninterrupted. Washington has secured its own heavy crude supply while simultaneously cutting off China’s.

The asymmetry is precise.

The global refining system doesn’t care about political narratives. It cares about molecular weight, sulfur content, and catalyst poisoning. The diesel crack spread is widening because the specific chemistry required to produce middle distillates efficiently has been removed from the supply chain.

Abundant light sweet crude from U.S. shale doesn’t solve a heavy sour crude deficit. The molecules are wrong.

If the United States can remove the head of state guaranteeing a deal, the deal itself becomes worthless. Beijing has lost its counterparty. Demanding repayment from a government that has just been decapitated by U.S. special forces is a futility.

The diesel crack spread will keep widening until either Venezuelan production resumes under U.S. control, Canadian heavy crude floods the market at narrowed discounts, or Chinese refineries shut down from feedstock starvation.

None of these outcomes favor Beijing.

The operation took thirty minutes. The consequences will compound for years.

References:

How U.S. forces captured Venezuelan leader Nicolás Maduro in Caracas

Maduro capture: What’s at stake for China’s economic interests in Venezuela

Won’t this just cause China to further increase the speed of electrification of its economy?

This is a level of understanding I just don’t get elsewhere and I read a lot. I really appreciate you and your coverage.