When Japan Sells, the World Shakes

When the world’s biggest creditor nation starts dumping foreign bonds, everyone should pay attention.

For decades, Japan’s bond market was the global anchor of stability—a zero-yield black hole that subsidized the rest of the world’s borrowing. Now it’s cracking. Long-dated Japanese government bonds are selling off violently. Auctions are failing. Yields are surging.

The global carry trade is unwinding, and the world’s most disciplined creditor is starting to retreat.

This isn’t just a Japan story. This is a sovereign debt inflection point.

The First Domino

Japan spent the better part of the last decade suppressing yields, loading up domestic investors with ultra-long bonds, and cultivating an ecosystem where interest rates didn’t matter—until they did. Now that the BOJ is tapering its bond purchases, the floor is falling out from under the JGB complex. The 40-year yield has surged to 3.6%, while the 30-year is flirting with 3.14% and the 20-year just recorded its weakest auction since 1987.

This is what happens when decades of yield repression meet the realities of demographic decline, fiscal strain, and investor exhaustion.

Natural Buyers? Not So Fast

Yes, Japan has massive domestic pools of capital—insurers, pensions, megabanks like Post Bank and Norinchukin, and giants like GPIF. But these institutions, once pushed into foreign assets by YCC and a flat yield curve, now face mark-to-market losses and capital constraints that make repatriation a slow grind.

According to IMF data:

Insurers alone hold over $500B in foreign bonds, with just 40% of that hedged.

Post Bank and Nochu hold a combined $700–800B, mostly hedged, but were driven abroad due to the flat curve.

GPIF, the whale among whales, has only ~25% of its portfolio in domestic bonds. It’s not exactly nimble.

Layer on hedging costs, illiquidity in long-dated JGBs, and the sheer scale of exposures, and what emerges is a fragile equilibrium: capital wants to return home—but doing so risks breaking the very market it’s meant to stabilize.

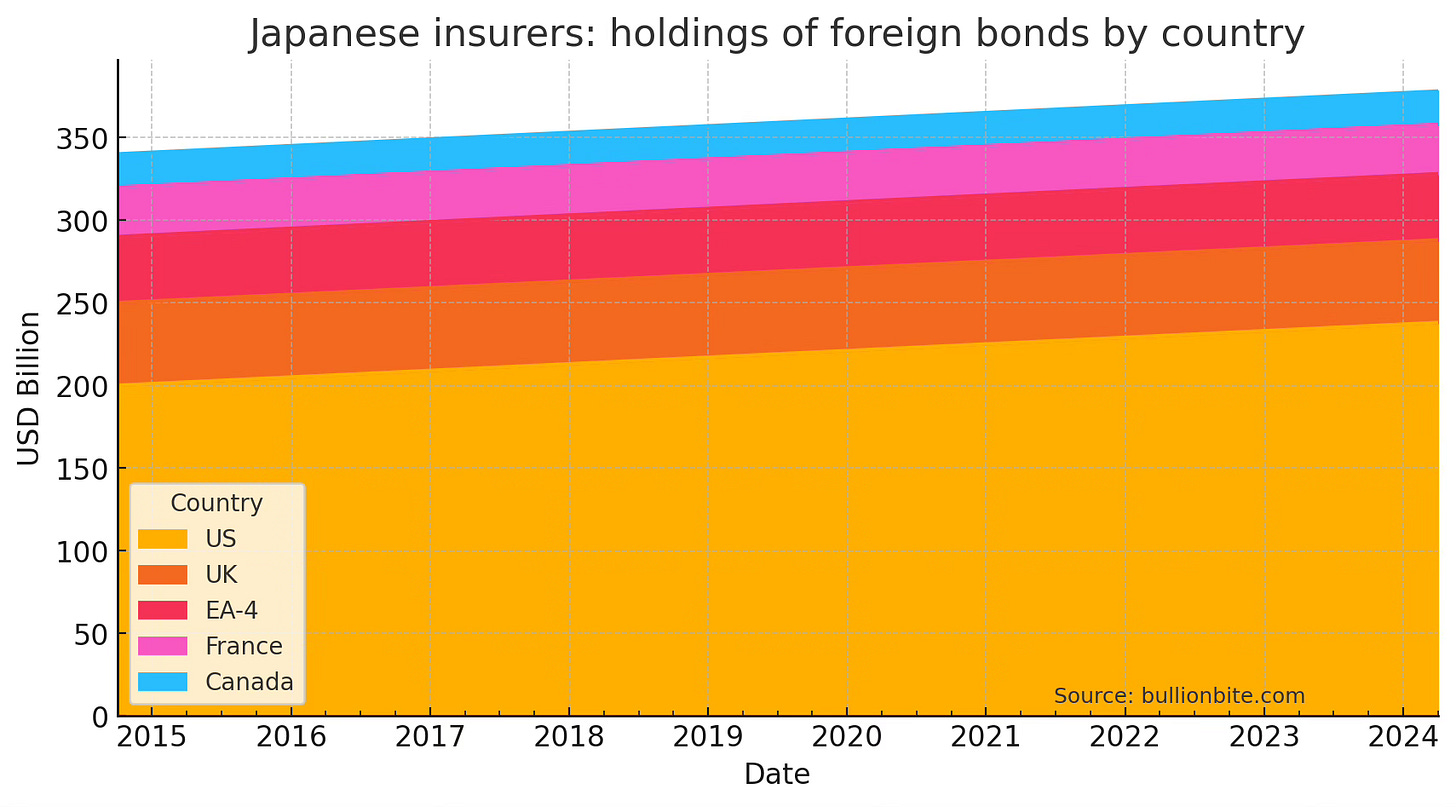

Japanese insurers didn’t just reach for yield—they reached globally. The breakdown below shows how foreign bond exposure is spread across major developed markets.

That accumulation, a byproduct of a decade under yield curve control, now stands squarely in the way of any smooth reallocation back into yen assets.

Add in the hedging costs, the illiquidity in long-dated JGBs, and the sheer scale of positions, and you get an uneasy stalemate: capital wants to come home, but doing so en masse risks flooding thin markets.

And it wasn’t just insurers. Banks, pension funds, and other institutional giants joined the foreign bond binge, as the sectoral breakdown makes clear.

The broader institutional footprint—visible below—underscores how widespread and entrenched this foreign bond exposure really is.

A Sovereign Debt Fork in the Road

The JGB implosion isn’t happening in isolation. It’s part of a bigger global inflection:

The US just suffered a weak 20-year auction of its own.

Global debt just surpassed $324 trillion.

Foreign investors are dumping JGBs and Treasuries alike.

Central banks are nearing the limits of monetary wizardry.

As Deutsche Bank recently noted, rising JGB yields are now siphoning capital away from US Treasuries. With Japan as the largest overseas holder of US debt ($1.13 trillion), this matters. The carry trade is unwinding. The foreign bid is weakening. And the yen is strengthening—even as US yields rise. That’s not normal. That’s a signal.

The Fiscal Reckoning Is Global

Japan has the highest debt-to-GDP ratio in the developed world. But it’s not alone in its fiscal excess. The US is running trillion-dollar deficits during peacetime. Europe is flirting with its own fiscal cliffs. And the fantasy that central banks can backstop everything is dying one bond auction at a time.

The implication? We may be entering a period of forced deleveraging and debt repricing across sovereign markets. Japan’s bond market just happens to be the opening salvo.

The Case for Long-Dated JGBs?

Ironically, in a world starved for real yield, 20- to 40-year JGBs yielding over 3% might look… attractive. Especially to domestic institutions with yen liabilities. Repatriation flows could stabilize the market—but only after some serious pain.

GPIF, Nochu, Post Bank, and insurers may start rotating back into JGBs, selling foreign equities and bonds. But that will be a slow, politically sensitive process. Meanwhile, volatility is likely to persist.

Unlike other indebted nations, Japan enters this bond market upheaval with a powerful structural advantage: it is the world’s largest net creditor.

Years of accumulated reserves and portfolio debt assets provide Japanese institutions with significant latent firepower. If long-dated JGBs become compelling enough, that capital can be redirected inward—potentially stabilizing the domestic market just when it matters most.

Japan’s reserve and portfolio asset growth highlights its structural net creditor position—a key buffer as global sovereign debt markets wobble.

The Global Feedback Loop

The world relied on Japan to keep rates low and liquidity flowing. If Japanese investors stop buying foreign debt and start repatriating capital, global rates rise. Risk assets suffer. And currencies—especially the dollar—get repriced.

Saravelos of Deutsche Bank sees the yen’s strength as the clearest signal yet: foreigners are quietly backing away from US debt, just as Japanese institutions shift their gaze inward.

And when Japan retreats, it doesn’t retreat alone.

The bond market is the mother of all markets. And right now, the mother is screaming.

Japan isn’t the end of the story. It’s the beginning of the next chapter.

Sovereign debt, once thought riskless, is now anything but. The credibility of central banks is crumbling. The world’s largest creditor nation is breaking ranks. If Japan is no longer willing to play the game, who is?

Buckle up. What’s coming isn’t a correction—it’s a sovereign debt realignment on a global scale.