The Epstein Files as a Geopolitical Weapon

The DOJ release, China's currency ambitions, and Australia caught in between.

Australia is building submarines to fight a navy it helps construct, paying for the privilege in that navy’s own currency. That is the centrepiece of Australian grand strategy in 2026.

The country sells iron ore to China, increasingly settles the trade in renminbi, and funnels the security dividends into AUKUS, the trilateral pact with the US and UK that is delivering nuclear-powered submarines meant to counter Chinese naval expansion. It has bet its prosperity on one great power and its security on another, at the precise moment both are starting to demand it pick a side. Three events in January made that contradiction impossible to ignore.

The US Department of Justice released 3.5 million pages of Epstein files. Within 24 hours, Beijing published the full text of a two-year-old Xi Jinping speech on building a financial powerhouse. And at Davos, Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney told the global elite the rules-based order was finished, calling the moment a rupture, not a transition.

Pick any one of those. It would take years to process. All three hit in the same week.

Senator Ron Wyden described the Epstein revelations as evidence of a pervasive culture of lawlessness on Wall Street. That phrase does more geopolitical work than any think tank paper published this decade. The released documents suggest that banks charged with policing the global financial system routinely bypassed their own protocols to accommodate what the files call the Epstein class. Not rogue employees. Systems. Compliance departments. Intelligence agencies that, according to the files, appeared to look the other way.

For Beijing, this is a gift. State media have spent years calling the Western rules-based order a hypocritical front. Now they have receipts. Millions of pages of them. Released by the American government itself.

Xi’s speech, published in the CCP journal Qiushi with exquisite timing, leans right into the opening. The concept of Yi Li, righteousness over profit, gets deployed not as philosophy but as brand positioning. Finance should serve the real economy, not sit on top of it like a parasite. After 2008, after the crypto collapses, after the Epstein files, that pitch lands differently in Jakarta and Brasilia than it does in Washington.

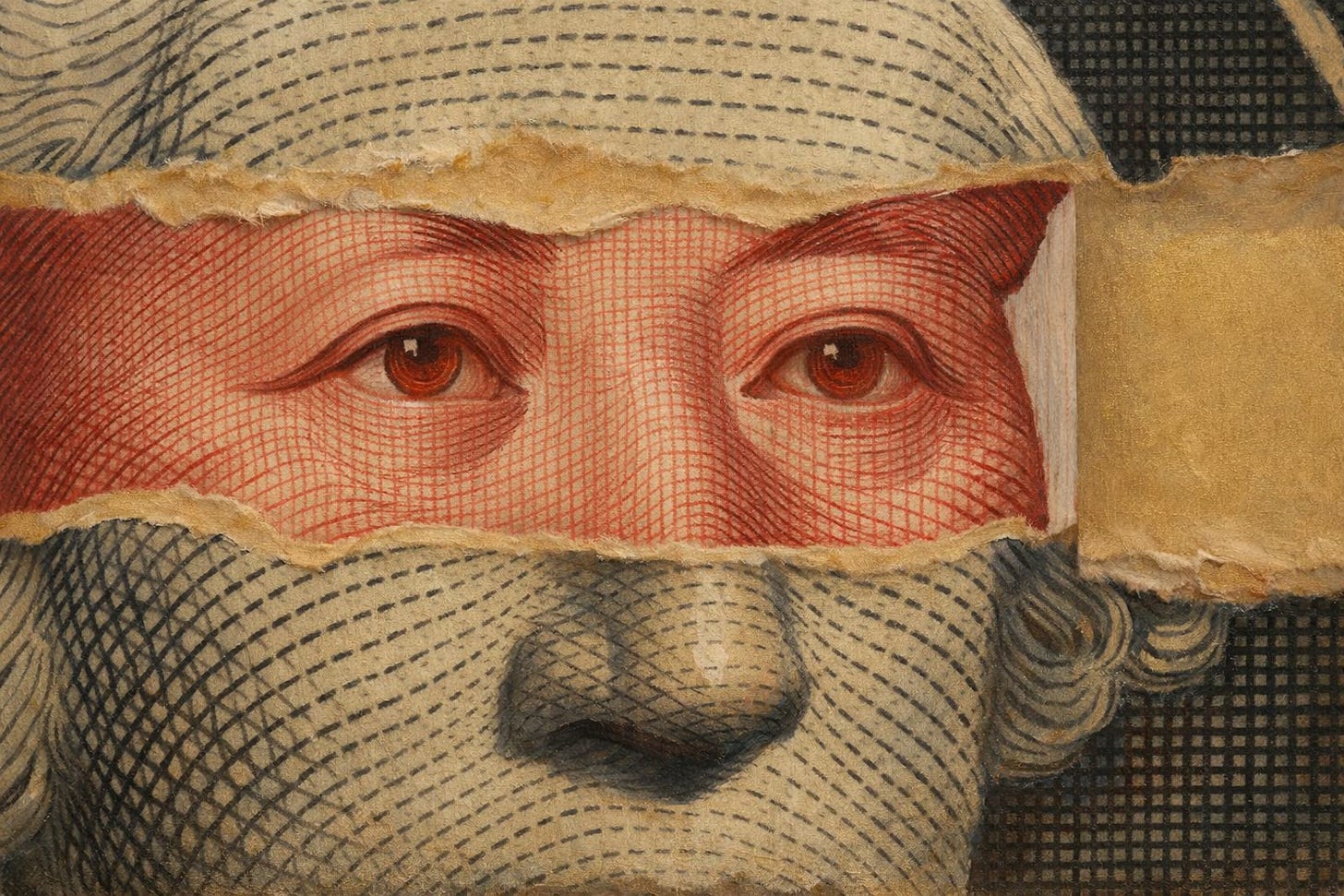

The first of Xi’s six directives is the one that matters: the renminbi must become a global reserve currency. Goldman Sachs estimates the yuan is about 25% undervalued on a trade basis. That is not a bug. It is stored energy. Years of suppressed appreciation that the People’s Bank of China can release slowly, making RMB assets more valuable for every country holding them.

For Australia, the sharpest edge of all this is the BHP deal.

Australia’s largest miner reportedly agreed to settle a third of its spot iron ore sales in renminbi. Iron ore is the country’s most valuable export. Every tonne used to move in US dollars. Not anymore. Analysts are calling it the start of a ferro-yuan system, commodity flows priced and settled in RMB, reinforcing China’s currency the way oil reinforced the dollar fifty years ago. For BHP, maybe it cuts transaction costs. For the country, it means a growing slice of national income now sits in a currency controlled by a state that has shown it will weaponize trade when it suits.

A University of Technology Sydney report found that only 0.2% of Australian exports were invoiced in RMB last financial year. Every major Australian bank has pulled out of Asia over the past decade. So if an Australian firm needs to hedge or settle in renminbi, it has to go through the local branch of a Chinese state-owned bank. The data on Australia’s most important trade relationship now lives on foreign ledgers. Regulators can barely see it.

Carney’s Davos speech named the problem. He said hegemons cannot continually monetize their relationships without pushing allies to hedge. His prescription, what he called variable geometry, meaning flexible, issue-by-issue coalitions among middle powers rather than rigid Cold War blocs, boiled down to: stop pretending the old alliances work. Australian Treasurer Jim Chalmers called the speech stunning. That word is doing a lot of heavy lifting, because Carney was describing the exact trap Australia is already sitting in.

Through AUKUS, Australia is bolting its military to the United States. Through its commodity trade, it is bolting its income to China. The iron ore that builds Chinese warships now settles in the currency that funds the Chinese state. The United States Studies Centre proposed a National Economic Security Agency to deal with this. Recommended strategic indispensability over spreading bets thin.

The Epstein files make even the values argument harder to sell. Australian leaders have long justified the American alliance on shared principles: democracy, rule of law, human rights. When the senior partner’s legal system is credibly accused of functioning as a shield for the connected rather than the vulnerable, that pitch starts to collapse. Beijing does not need its moral governance line believed in Canberra. It just needs the American alternative doubted.

The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born: now is the time of monsters. Australia is not a monster. It is something worse off: a middle power that bet its security on one giant and its prosperity on another, right as both start demanding it pick a side.