Owning Less in an Age of More

From one-income homes to five-income leases.

There’s this thing that happens at family gatherings. Someone starts waxing nostalgic about the 1950s. Back when you could buy a house on a factory salary, they’ll say. When mom stayed home and dad’s paycheck covered everything.

And yeah, there’s something seductive about that narrative. The neat suburban lawns. The gleaming Chevrolets. June Cleaver vacuuming in pearls. It’s all very tidy. Very unlike trying to split rent three ways while your student loans hover like a storm cloud.

But here’s the thing: the 1950s middle class would be considered straight-up poor by today’s standards. Not can’t afford avocado toast poor. We’re talking no indoor plumbing in rural areas poor.

The median household income in 1955, adjusted for inflation? Between $25k and $30k. Today we’re at $82k. Before you start typing that angry comment about million-dollar houses, let’s walk through what that actually bought you.

Your house (if you owned one, only half of Americans did) was 970 square feet. Total. These weren’t sprawling suburban dreams. They were boxes. Tiny boxes we only remember fondly because the well-built ones survived.

Air conditioning? Luxury. Dishwasher? Dream on. Multiple bathrooms? One toilet for six people was standard. Food ate up 20% of income vs. 10% today. Clothing was 8% vs. 2% now. Those Norman Rockwell families? Pure fantasy. Reality was dad’s two work shirts, mom making clothes from flour sacks, and everyone stuffing cardboard in their shoes by winter.

Yet.

You could buy a house on one income.

A New York cop could own a home. A divorced mother working part-time could keep a roof over five kids in what’s now million-dollar territory. Were they poor? Absolutely. Sleeping around the fireplace poor. But they owned that fireplace.

Consider this: grandparents in the ’50s buying 20 acres. Grandpa worked on boats, did some farming. Grandma at the bank. They built a house, a barn, had four kids, newer cars, a boat. Sure, they never ate out. Vacations meant camping, not Cancún. But that stability on working-class jobs? Incomprehensible now.

College is where it gets weird. Only 4% had bachelor’s degrees in 1960 vs. 40% today. Sounds like progress until you realize you didn’t NEED a degree then. You could walk out of high school into a job that supported a family. Not a gig, not a hustle. A job. With a pension.

Though let’s be real about college. Yeah, tuition was cheaper, about $6,200 for four years adjusted. But when you’re making $30k trying to feed six kids, that might as well be $600k. Difference is, you had options.

Found this hospital bill from 1941—$500 for appendicitis, which is $11k today. Expensive, sure, but that’s everything. The surgery, the stay, all of it. No insurance companies playing phone tag. No seventeen separate bills from seventeen different departments. Just one bill that would financially devastate you, instead of the current seventeen that will.

Is that… better? Hard to say.

What’s brutal is this tension between material poverty and economic security. Life is objectively better now. We’re typing on devices containing all human knowledge. Apartments have AC, dishwashers, in-unit laundry. Strawberries in December. Korean dramas at 2 AM.

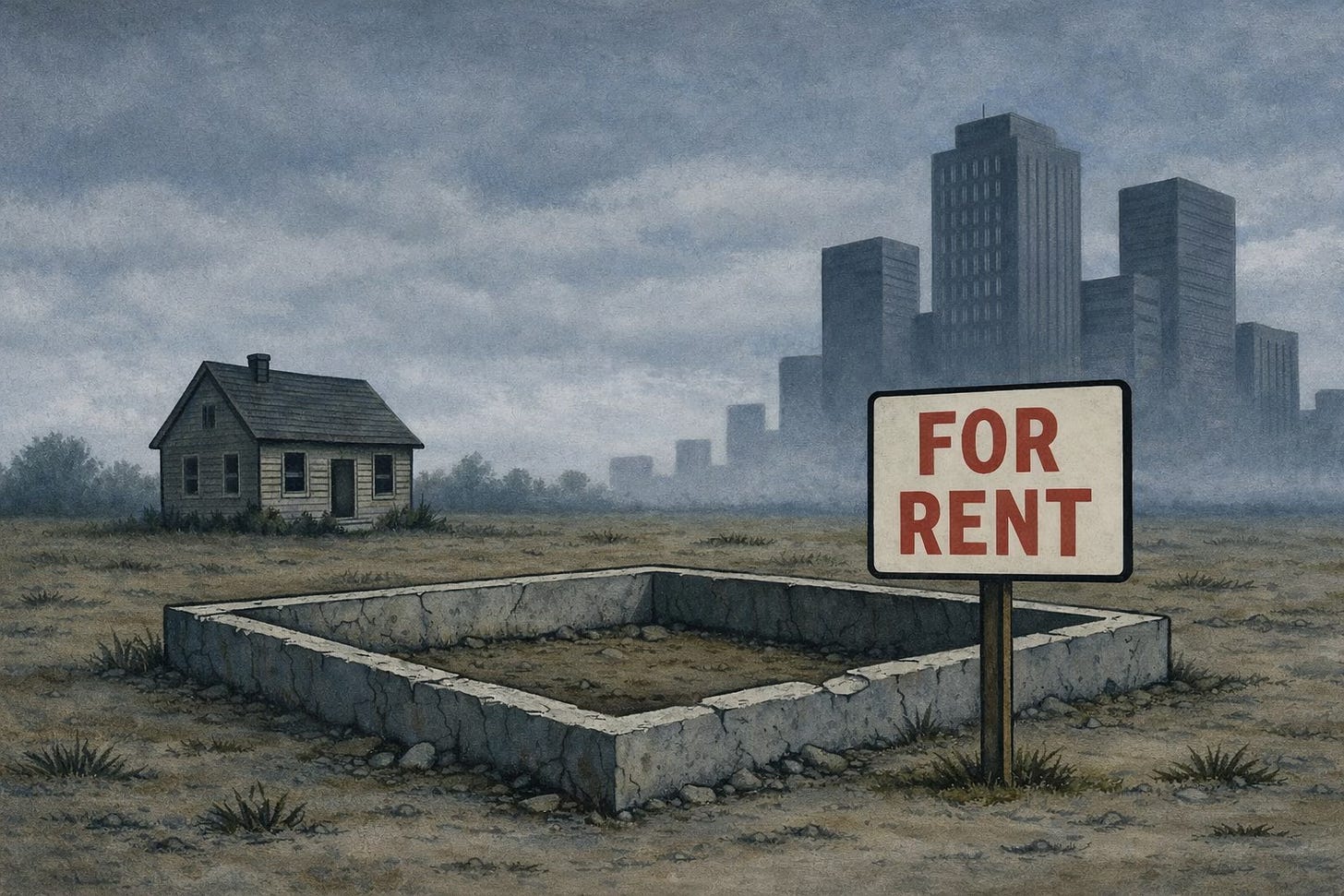

But homeownership? For someone doing everything right—good college, useful degree, steady job, earning more than their parents ever did? Feels about as attainable as yacht ownership.

There’s something psychologically crushing about that. Something square footage stats can’t capture.

The arguments always go the same way: You have iPhones, stop complaining vs. I’d trade my iPhone for housing. Both miss the point. We traded security for consumer goods.

Nobody mentions how many expenses didn’t exist then. No internet bill, cell plans, streaming services, software subscriptions. Just water, electric, maybe gas. Simpler budget because simpler life.

Sometimes it feels like comparing apples to smartphones. Like asking if medieval peasants were happier than office workers. The question barely computes.

The ‘50s sucked in ways we’ve forgotten. Polio. Black families excluded from suburban dreams. Women couldn’t get credit cards. Gay people hiding. Mental health treatment was barbaric.

But there was this moment, really just for straight white families, where one regular job bought you everything. House, car, kids, retirement. The package.

That’s gone. Probably forever. Maybe that’s fine; that world was built on exclusion and exploitation. But the nostalgia makes sense, even knowing it’s mostly fantasy. Something deeply human about longing for simplicity that never really existed.

Everyone’s arguing about inflation calculators and whether microwaves count as progress. Everyone’s uncle bought a house for nothing.

Every generation thinks the last had it easier and the next has it too easy. We’re all stumbling through our moment, romanticizing losses, ignoring gains.

Still. Twenty acres on a mechanic’s salary.

Wild.