China Isn’t Lending. It’s Collecting.

What was once sold as development finance now looks a lot more like leverage.

China didn’t just build bridges. It built debt obligations that now weigh heavily on its borrowers.

A decade after the height of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Beijing has shifted from provider of credit to enforcer of repayments. The same countries that once welcomed Chinese financing are now facing repayment pressure. In 2025, this dynamic intensifies.

This transformation isn’t based on theory. The numbers speak clearly. At least $35 billion will be paid to China this year. $22 billion of that will come from the world’s poorest nations. What once began as development assistance has now become a repayment regime.

In 2016, China was providing over $50 billion annually in loans. Infrastructure investments spread across continents. The goal was framed as development. The underlying drivers included industrial overcapacity and the need for outbound capital.

By 2018, defaults increased. Project execution slowed. China reduced its lending volume. As of now, annual new lending has dropped to around $7 billion. At the same time, repayment demands have increased.

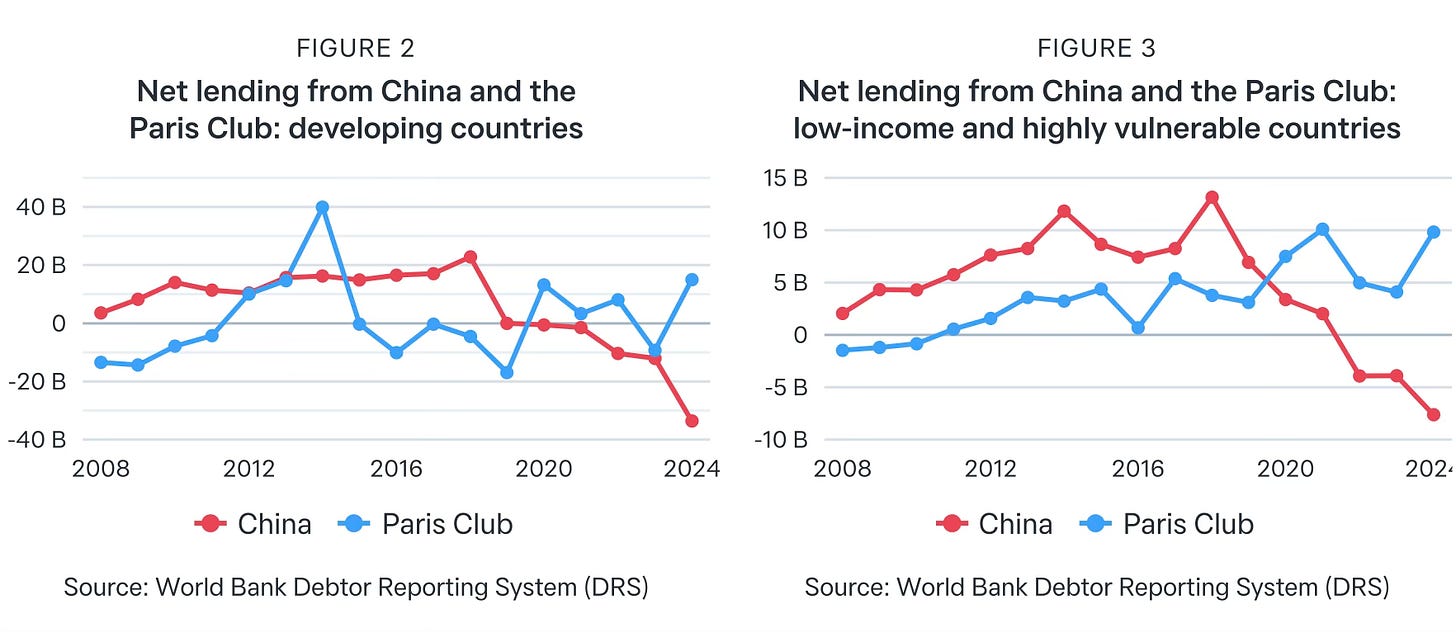

China no longer operates as a net lender. Its role has shifted. In 2023, it was collecting more from 60 developing nations than it was lending.

Chinese loan terms have always differed from Western norms. While Western nations often provided grants, China preferred loans. These loans were typically less transparent and included short grace periods.

As these grace periods expire, national budgets are strained. Spending on public services like health and education is being reduced. Political consequences are emerging in several debtor countries.

Sri Lanka defaulted. Kenya’s debt relationship with China became a political issue. Pakistan has significant outstanding obligations. China’s financial institutions are requesting repayment, and its leadership is under increasing international scrutiny. The response has been a mix of deferrals and partial restructuring, though full cancellations remain rare.

Some countries still receive Chinese loans. These are mainly nations with strategic proximity or valuable natural resources. Countries like Mongolia and Laos remain in the picture. So do exporters of key minerals, including Argentina, Brazil, DR Congo, and Indonesia.

The shift from global builder to selective financier marks a new era in China’s external economic strategy.

Western commentators often refer to these developments as examples of “debt-trap diplomacy.” One frequently cited case is the lease of Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port.

Researchers such as Deborah Brautigam point out that the broader picture is more complex. There is little empirical evidence to support claims of intentional asset seizure. In many instances, borrower governments actively pursued the loans without adequate planning.

Even so, there are valid concerns about how Chinese loans are structured. Contracts tend to be confidential. Coordination with other creditors is limited. These factors make debt resolution harder.

At the same time, Western engagement has declined. U.S. foreign aid has remained flat. Europe is more inward-focused. The IMF and World Bank are still involved, but their capacity is limited compared to China’s footprint.

Criticism of China’s lending model has grown, but few concrete alternatives have been offered. Many developing nations remain exposed, with limited options.

As of 2023, over 3.3 billion people live in countries that allocate more to external debt service than to health or education.

Global development efforts have slowed. Payments to China are one piece of this larger challenge. Many low-income countries lack access to concessional support to manage their obligations.

If current trends continue through 2025, fiscal pressure will deepen. Debt servicing will limit economic recovery. Social and political risks will rise in countries already under stress.

China’s position today reflects a significant shift. It is now collecting more than it provides. This pattern is unlikely to change soon. The original loan terms are maturing, and Beijing appears cautious about new exposure.

These conditions highlight the need for updated international financial tools. Without broader restructuring options and renewed aid flows, many developing economies will remain constrained.

Without coordinated pressure and reform, debt diplomacy will harden into permanent leverage—and the developing world will be paying for it long after the bridges crumble.

Sources: World Bank, AidData, Lowy Institute