August 1 Will Break Something

It just won’t be the countries you think.

August 1st is coming fast, and with it the most aggressive tariff regime in modern American history. While markets have grown somewhat numb to Trump’s trade theatrics, the sheer scope of what’s about to hit suggests we’re entering uncharted territory.

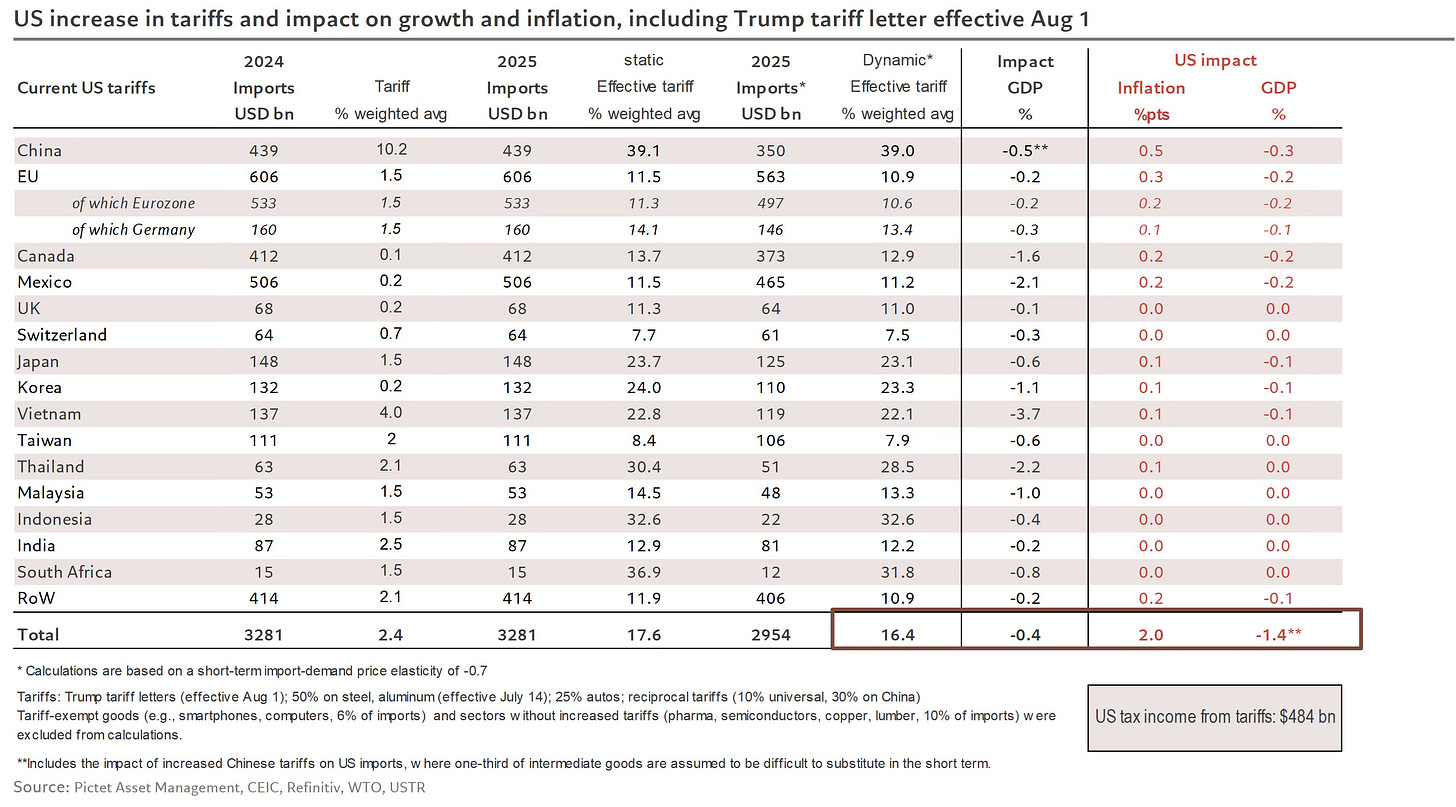

Myanmar and Laos face a crushing 40% tariff wall in global trade. Thailand and Cambodia get slammed with 36%. Bangladesh and Serbia aren’t far behind at 35%, with Indonesia catching a 32% hit. Even traditional allies like Japan and South Korea find themselves staring down 25% rates, alongside Malaysia, Tunisia, and Kazakhstan. China’s 30% and Vietnam’s 20% were just the opening act.

What’s particularly striking is how these rates aren’t emerging from any coherent trade strategy. Despite being marketed as trade agreements, these are unilateral impositions dressed up in diplomatic language. The Vietnam deal perfectly illustrates this charade. It includes a punitive 20% surcharge specifically targeting products that might be Chinese goods in disguise, effectively closing off what has become a major trade route in recent years.

We’re now looking at a weighted average tariff rate nearing 20%. Yet markets don’t seem to have priced this in fully. Once these measures take effect, there’s a good chance we’ll see some sharp and uncomfortable corrections.

Just last week, the Trump administration passed tax cuts, supposedly to stimulate the domestic economy. But those gains are already being offset by tariffs that act as a consumption tax on American households. It’s fiscal policy undoing itself in real time.

Still, not everything is set to unravel immediately. One interesting dynamic is how much time companies have had to prepare. Thanks to the drawn-out timeline and repeated delays, many have built up stockpiles. That buffer could help smooth the price increases, letting them phase in more gradually rather than all at once.

Japan offers perhaps the most striking example of how companies are adapting.

Faced with a 25% tariff, Japanese automakers have made a bold move. They’ve cut their export prices to the US by up to 20%, essentially eating the tariff themselves. It’s a gamble that trades margin for volume, with the hope that overall profits can be preserved. More importantly, it shifts the cost from US consumers to Japanese shareholders. That creates a deflationary offset to the inflationary pressure building elsewhere.

This strategy highlights how the impact of tariffs is far from uniform. Industries with strong margins and intense competition may be able to absorb the costs, at least for a while. Others, especially those with thinner margins or limited competition, will have little choice but to pass the costs along.

The European Union’s negotiations provide another window into the global scramble for damage control. Even securing a good deal means accepting a 10% tariff rate, still a significant cost increase that will ripple through supply chains and consumer prices.

Canada’s elimination of its digital services tax reveals the broader geopolitical leverage these tariffs create. By removing this barrier, Canada has essentially handed American software companies a competitive advantage in the Canadian market. It’s a preview of how trade threats can reshape entire sectors, with US tech firms emerging as unexpected beneficiaries of an otherwise destructive policy.

The software sector’s position highlights a broader pattern: while most industries face headwinds from rising trade barriers, some segments could see their competitive positions improve. American software companies, in particular, stand to benefit from both the elimination of foreign service taxes and the general shift toward domestic solutions as imported alternatives become more expensive.

This creates an interesting investment thesis. While broad market indices might struggle with the inflationary pressures and economic uncertainty, specific sectors could outperform dramatically.

Software companies with strong domestic positions and minimal import dependencies look particularly attractive. Meanwhile, commodity-focused businesses might find themselves benefiting from dollar weakness and renewed interest in tangible assets.

The currency implications are equally fascinating. The dollar’s strength has been predicated partly on America’s position as the global trade hub, but these tariffs could fundamentally alter that dynamic. If the US becomes a less attractive trading partner, the dollar’s reserve currency status could face genuine challenges for the first time in decades.

The timing couldn’t be more interesting. Markets have shown remarkable resilience to Trump’s trade threats, partly because they’ve heard this song before. But the scale and simultaneity of these new tariffs represent something qualitatively different. We’re not talking about targeted actions against specific countries or industries but a broadside against the entire global trading system.

The inventory buildup strategy that many companies have adopted buys time, but it doesn’t eliminate the fundamental problem. Eventually, those stockpiles will run down, and the full cost of these tariffs will hit. The question isn’t whether we’ll see price increases, but how quickly they’ll compound and where they’ll hit hardest.

To put the scope and impact in perspective, the chart below summarizes projected import levels, effective tariff rates, and estimated effects on both inflation and GDP:

What’s perhaps most concerning is the signal this sends about American economic policy more broadly. These aren’t the actions of a country confident in its competitive position. They’re the desperate moves of an economy that’s lost faith in its ability to compete on level terms.

The global response will be crucial. If other countries retaliate with their own tariffs, we could see a genuine breakdown in the multilateral trading system that has underpinned global prosperity for decades. The Japanese approach of absorbing costs rather than retaliating might offer a template for avoiding this worst-case scenario, but it requires enormous financial capacity and market position that most countries simply don’t have.

For investors, this environment demands a fundamental rethinking of assumptions. The low-inflation, high-globalization regime that has dominated market thinking for the past three decades is giving way to something much more volatile and uncertain.

Portfolio construction needs to account for currency instability, supply chain disruptions, and the possibility of sustained higher inflation. The August 1st deadline isn’t just another date on the trade calendar but potentially the moment when the post-Cold War economic order begins its transformation into something much more fragmented and confrontational.

Trump’s tariff gambit represents the most significant shift in American trade policy since the 1930s, and like that earlier experiment, it’s being launched with enormous confidence but little understanding of the complex feedback loops it will trigger. The next few months will reveal whether this bold strategy can deliver the promised benefits, or whether it will simply accelerate America’s relative economic decline while making everyone poorer in the process.